CHARLES COOKE: Why the Outrage Over the Cuts at the Washington Post Is So Annoying.

I have been trying to put my finger on exactly why I have found the outrage over the cuts at the Washington Post so annoying, and in searching for that answer, I have instead found a whole fist. So here goes: The outrage over the cuts at the Washington Post is annoying because the gap between the self-regard of those who were fired and the contributions of those who were fired is so enormous as to beggar belief. On days such as yesterday, Twitter is filled to the brim with “I was just laid off” posts, as though one had stumbled upon a battlefield strewn with the wounded — except, unlike on a battlefield, the wounded are all talking to one another in cloying, self-congratulatory tones. The result is a veritable web of grotesque and sycophantic encomia that does not stand up to even the slightest evaluation.

Don’t believe me? Click through on one of those posts, scroll past the pinned advertisement for the newspaper’s union, and look up the user’s name in the Post’s archive. If you do, you’ll typically learn that the person who is being praised as a “brilliant” and “talented” journalist who did “great work” has a job description like “sits at the intersection of civil rights and cooking,” that they wrote four things in the last two months, and that two of them were about how alligators are racist.

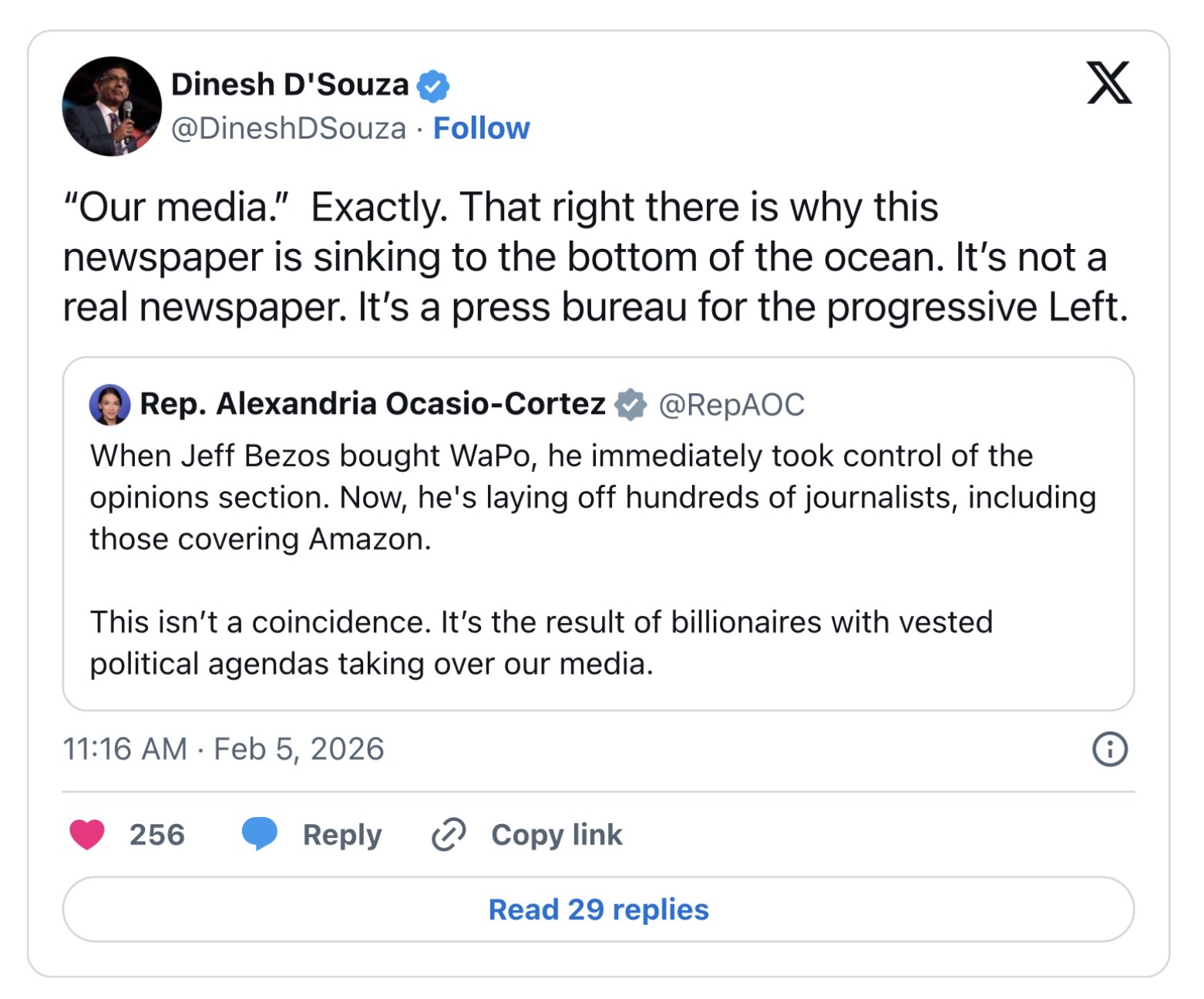

To get a sense of why the Post failed with its intended audience of leftists, that reference flew right past the head of the “New York-based journalist covering media for Semafor:”

Miller’s tweet continues, “Now do you see you and the media’s problem?”

But then, as T. Becket Adams wrote last November: When crazy is too crazy even for the base.

It’s one thing for Democrats to live in a bubble where they don’t know or understand what Republicans believe. But how can they not know what’s happening in their own backyard? How have they insulated themselves so well that their first reaction to learning about what Democratic politicians are doing is to assume it’s some kind of Republican dirty trick?

This phenomenon goes far beyond too-online comedians and sloppy journalists. In fact, GOP pollsters say the disconnect between what Democratic legislators support and what Democratic voters know of their own party has made it much more difficult to collect accurate survey data.

“When you outline the Democratic agenda, you have to water it down, because in both polling and focus groups, people just don’t believe it,” a Republican source told Park MacDougald for Tablet magazine in 2024, before the election. “They are critical of things like boys in girls’ sports, but they tune out stuff about schools not informing parents about transitioning their children. They just don’t believe it’s true. It can’t be.”

But it is.

But reality catches up eventually. Or as Scott McKay writes at the American Spectator: You Can’t Go on Destroying Wealth Forever, You Know. Ultimately, There Are Consequences.

Here’s hoping the Post employees can find gainful employment. But along the way, let’s also hope they learn a lesson from the decline of their former employer — which is that serving an ideology, rather than the public good or the needs of the market, ultimately isn’t a sustainable pursuit.

As for Billie Eilish, one surmises she’ll be fine — whether the tribesmen of the Tongva repossess her house or not. Thought we do wish the best of luck to her in expanding her audience beyond mentally deranged Gen Z females. She’ll need it.

By the way, the excesses of the Clinton-obsessed American Spectator of the 1990s and its spectacular crash and burn after he left office were a warning the Washington Post should have headed when it went full-bore TDS a decade ago: The Life and Death ofThe American Spectator.