JOE NOCERA: The Luxurious Death Rattle of the Great American Magazine.

When he became the editor of Vanity Fair in 1992, [Graydon] Carter could have put a stop to the spending culture he inherited from his predecessor, Tina Brown. That would have made the magazine much more profitable. (David Remnick did exactly that when he replaced Brown as editor of The New Yorker in 1998, turning a money-losing magazine into a profitable one.) But Carter liked the lifestyle too much to let go of it. He liked flying on the Concorde when he went to Europe (round-trip ticket: $12,000). He liked having two assistants instead of one. He liked having his own personal driver, and he liked presiding over Vanity Fair’s uber-expensive Oscar party.

And so, Carter set the tone. “At Vanity Fair in those early days, anyone on the editorial floor could take out pretty much any amount of reasonable cash just by signing a chit,” he writes. “Flowers went to contributors at an astounding rate, sometimes just for turning a story in on time.”

He cites approvingly how his deputy, Aimée Bell, gamed expense accounting at Condé Nast: “She figured out early that the accountants budgeted your expenses based on what you spent the previous year,” he writes. “That meant that what you needed to do was set a high bar early and build on a large amount of expenses.”

He adds: “And I was fine with that.”

“This, in its essence, was Vanity Fair.”

Of course, Vanity Fair spent money on journalism, too—gobs of it.

He paid Dominick Dunne $500,000 a year to cover the O.J. Simpson and the Menendez brothers trials, “plus generous expenses and months of free and continuous accommodation at the Chateau Marmont or the Beverly Hills Hotel.” He recruited Michael Lewis and a half dozen other brand-name writers who were paid at least as much. He even proudly recounts the time Vanity Fair pursued a major story about Lloyd’s of London, the insurance company, “which may have been the most expensive per word magazine story ever written.” And it never ran! To hear Carter tell it, this is what you had to do: To get the best stories, you needed the best writers, and to get them and their stories, you had to spend lots and lots of money.

After five years working for Art Cooper, I moved to Time Inc.’s business magazine, Fortune. For the first half of my tenure, the good times rolled. Because Time Inc. was a public company, the editors were more conscious of profits than Condé Nast editors, but we flew business class, had staff retreats in the Virgin Islands, and sometimes spent months reporting stories, without thinking too much about it. Unfortunately, the other thing we weren’t thinking about was the prospect that the internet was about to eat our lunch.

In a non-paywalled article from 2009, John Podhoretz talked about his salad days at Time magazine in the 1980s as if it were something out of the Court of Versailles:

Time Inc., the parent company of Time, was flush then. Very, very, very flush. So flush that the first week I was there, the World section had a farewell lunch for a writer who was being sent to Paris to serve as bureau chief…at Lutece, the most expensive restaurant in Manhattan, for 50 people.So flush that if you stayed past 8, you could take a limousine home…and take it anywhere, including to the Hamptons if you had weekend plans there. So flush that if a writer who lived, say, in suburban Connecticut, stayed late writing his article that week, he could stay in town at a hotel of his choice. So flush that, when I turned in an expense account covering my first month with a $32 charge on it for two books I’d bought for research purposes, my boss closed her office door and told me never to submit a report asking for less than $300 back, because it would make everybody else look bad. So flush when its editor-in-chief, the late Henry Grunwald, went to visit the facilities of a new publication called TV Cable Week that was based in White Plains, a 40 minute drive from the Time Life Building, he arrived by helicopter—and when he grew bored by the tour, he said to his aide, “Get me my helicopter.”

The pre-Web era of mass media also allowed old media to be bottle up a story rather tightly. The dismantling of the Condé Nast empire, and other slick glossy magazines has implications beyond merely fashion, as Lee Smith wrote in his perceptive October 2017 article on the fall of Harvey Weinstein, “The Human Stain:”

A friend reminds me that there was a period when Miramax bought the rights to every big story published in magazines throughout the city. Why mess with Weinstein when that big new female star you’re trying to wrangle for the June cover is headlining a Miramax release? Do you think that glossy magazine editor who threw the swankiest Oscar party in Hollywood was trying to “nail down” the Weinstein story? Right, just like the hundreds of journalists who were ferried across the river for the big party at the Statue of Liberty to celebrate the premiere of Talk—they were all there sipping champagne and sniffing coke with models in order to “nail down” the story about how their host was a rapist.

That’s why the story about Harvey Weinstein finally broke now. It’s because the media industry that once protected him has collapsed. The magazines that used to publish the stories Miramax optioned can’t afford to pay for the kind of reporting and storytelling that translates into screenplays. They’re broke because Facebook and Google have swallowed all the digital advertising money that was supposed to save the press as print advertising continued to tank.

Look at Vanity Fair, basically the in-house Miramax organ that Tina failed to make Talk: Condé Nast demanded massive staff cuts from Graydon Carter and he quit. He knows they’re going to turn his aspirational bible into a blog, a fate likely shared by most (if not all) of the Condé Nast books.

Si Newhouse, magazine publishing’s last Medici, died last week, and who knows what will happen to Condé now. There are no more journalists; there are just bloggers scrounging for the crumbs Silicon Valley leaves them. Who’s going to make a movie out of a Vox column? So what does anyone in today’s media ecosystem owe Harvey Weinstein? And besides, it’s good story, right? “Downfall of a media Mogul.” Maybe there’s even a movie in it.

At the Yale Review this month, Bryan Burrough also writes about “Vanity Fair’s Heyday: I was once paid six figures to write an article—now what?”

Without straining, Graydon nicely positions his Vanity Fair in the flows of its day. Its ethos and popularity in the 1990s and 2000s were a sort of coda to the “New Journalism” perfected by Esquire during the 1960s and 1970s, when writers like Tom Wolfe and Gay Talese produced long, probing articles and in-depth profiles. Their style of writing went beyond the staid reporting and hard facts that readers had come to expect in print. Instead, they imbued their pieces with the stuff of novels: immersive stories, lyrical writing, vibrant descriptions, pacing on a par with the best propulsive fiction.

Vanity Fair embraced New Journalism, but as Graydon puts it in his book, it also “had an asset that no other magazine had in Annie Leibovitz. Annie was already a legend, a photographic visionary of huge gifts.” Leibovitz pushed the boundaries of what made a newsstand cover, from the arresting group photography showcased on Vanity Fair’s annual Hollywood Issue to its iconic image of a pregnant Demi Moore. The magazine mattered, especially in Hollywood and New York.

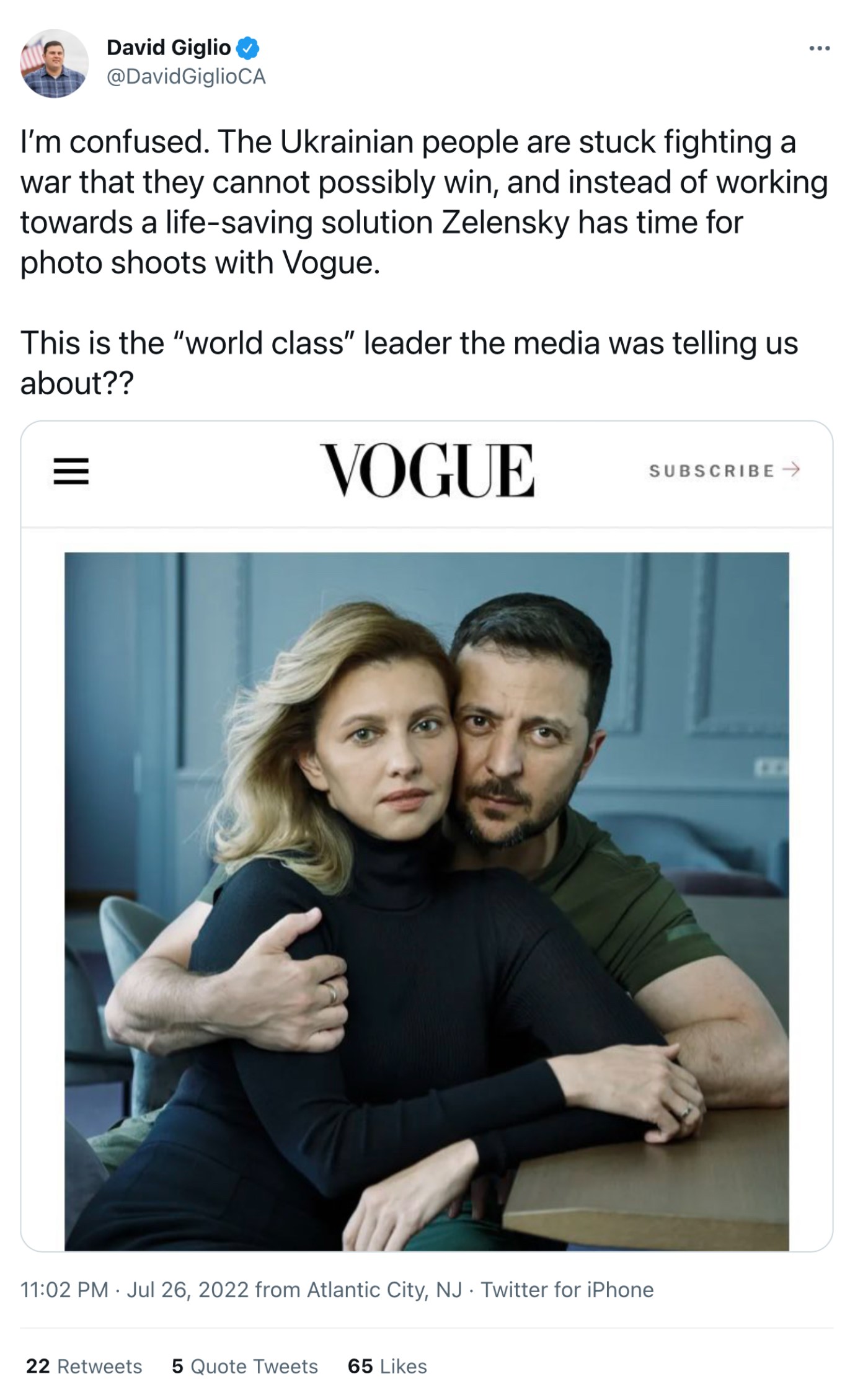

In more recent years, after her glamorous photoshoots led to the death knell of Robert “Beto” O’Rourke’s presidential bid and caused many in America to question Volodymyr Zelensky’s seriousness, Iowahawk quipped, “Whom the gods would destroy they first make pose for Annie Leibovitz.”