ALMOST ALWAYS A VERY HARD DECISION: Reflections of a Newsman.

I saw this article where country singer Ashley Judd talked about being on the “other side” of coverage of tragedies. It made me take pause and reflect.

As a former photojournalist turned newsroom lawyer, I’ve had to wrestle with this from time to time. My watch-words (especially in the Media Law and Ethics classes I teach) has always been “good taste and common sense win the day.”

But it’s always a tough call. My dear friend, the late Hal Buell was the long-time Photo Chief for the Associated Press. A truly decent guy in every way. When the legendary Nick Ut made the iconic news picture below, Hal told me years later that they debated for several hours about whether they should move the file on the wire.

(Credit: Nick Ut/AP under Creative Commons license)

They decided that despite its somewhat gruesome and certainly invasive nature, it depicted a moment too important to keep from the public. IIRC, some newspaper members simply chose not to run it.

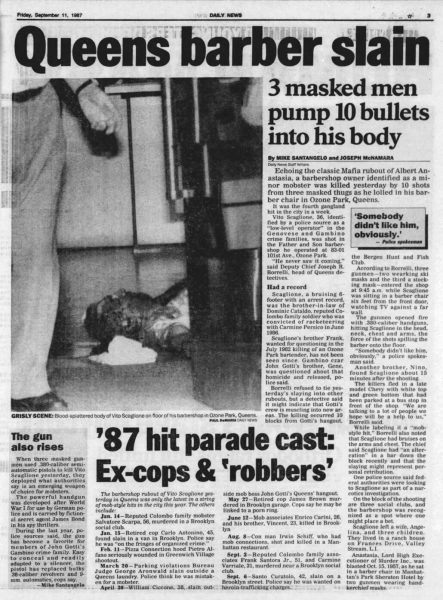

Flash forward a few years to the wild and wooly ’80’s. The standard became “if it bleeds, it leads.” Little thought was given to the sensitivities of the victim’s families, let alone the readers. Photographs like this were common:

(Credit: Paul DeMaria/NYDN via Wikimedia Commons)

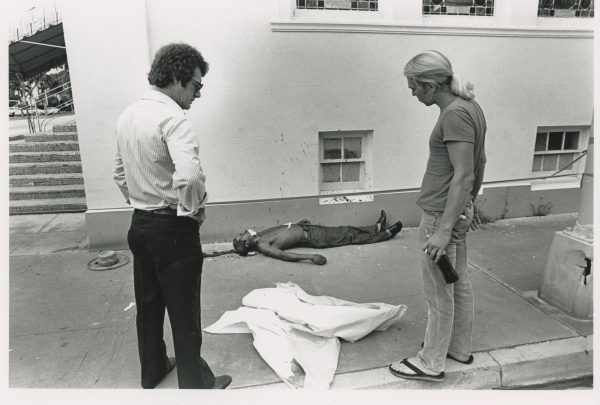

As a shooter myself, I was guilty of making pictures that today might be “insensitive.” I made the photo below after hearing a police call of a shooting outside an elementary school:

(Credit: Charles Glasser/Miami Beach Sun)

Apparently this fellow was a Marielito who owed about $50 to another drug dealer. Without warning, the murderer (never caught) simply walked up behind this guy and pumped a few .38 rounds into the back of his head. (FYI: Years later, Facebook blocked this photo from view for violating “community standards.”)

Did I consider anyone’s “privacy”? Hell, it was on a public sidewalk (in front of a school, no less) and the guy wasn’t a “somebody.” No relatives to complain, no objections from readers, I even won a Florida Press Club in Spot News award for it.

Let’s flash forward to my being a newsroom lawyer a decade or so later. I’m the Global Media Counsel for Bloomberg News. In the early days of the Enron collapse, one of the top executives — a real Boy Scout — committed suicide. An outstanding reporter named Loren Steffy, got a hold of his suicide note from the Sugarland PD. What to do?

The family’s lawyer begged us not to publish it. The note itself revealed nothing personal, and didn’t name names about Enron. I had a long, deep discussion with the Editor-in-Chief. If we didn’t publish, I argued, the family would be subjected to endless conspiracy theories. By publishing, we could put the matter of his suicide to rest. He knew bad things were done, as an honest guy he couldn’t deal with it, and it was going to get worse: He wanted to apologize to his family.

We ran the note. Thoughts?

UPDATE (From Ed): 50 years on: Revisiting the myths of the ‘Napalm Girl,’ a photo ‘that doesn’t rest.’

The napalm attack was carried out by propeller-driven Skyraider aircraft of the South Vietnamese Air Force trying to roust communist forces dug in near the village – as news accounts at the time made clear.

The headline over the New York Times report from Trang Bang said: “South Vietnamese Drop Napalm on Own Troops.”

The Chicago Tribune front page of June 9, 1972, stated the “napalm [was] dropped by a Vietnamese air force Skyraider diving onto the wrong target.”

Christopher Wain, a veteran British journalist, wrote in a dispatch for United Press International: “These were South Vietnamese planes dropping napalm on South Vietnamese peasants and troops.”

The myth of American culpability at Trang Bang began taking hold during the 1972 presidential campaign, when Democratic candidate George McGovern referred to the photograph in a televised speech. The napalm that badly burned Kim Phuc, he declared, had been “dropped in the name of America.”

McGovern’s metaphoric claim anticipated similar assertions, including Susan Sontag’s statement in her 1973 book “On Photography,” that Kim Phuc had been “sprayed by American napalm.”

(The Associated Press, in an article posted online yesterday, erroneously described the aerial attack at Trang Bang as “an American napalm strike on a Vietnamese hamlet.” See screenshot nearby. The news agency later in the day corrected the error after it was noted on Twitter.)

Read the whole thing.