I’LL TAKE HEADLINES FROM EARLY 1945 FOR $500, ALEX: Germany, Growing Desperate.

Well before the events in Gaza, Germany was nervous over migration. Today, 24 million of Germany’s roughly 80 million people—almost 30%—are of “migrant background,” and 2.7 million migrants settled in the country in 2022 alone. The demographic transformation of the West that began slowly with European decolonization and American civil rights has accelerated over the past decade and a half. Two events stand out: First, the 2011 Anglo-Franco-American invasion of Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya, carried out over the strong objection of then-German chancellor Angela Merkel. Barack Obama’s NATO “victory,” which culminated in the killing of Gaddafi and three of his sons, has proved almost as damaging to the West as George W. Bush’s Iraq defeat. It delivered the Tripolitan coast to smuggling mafias and thus opened the prospect of residence in Europe to the entire African continent, which is projected to add a billion people before mid-century.

A second key event was the huge migration of refugees from the Syrian war in 2015. Merkel welcomed the migrants in the name of a German Willkommenskultur, or “culture of welcome.” By this she seemed to mean a less focused version of the postwar tolerance for others that Habeck would lay out in his early November speech about Israel. Of course, if Germany really does have the responsibilities that Habeck and Merkel describe, then its immigration policy has been reckless. The perverse effect of Merkel’s invitation was to summon others from throughout the Muslim world who had nothing to do with the Syrian wars—Pakistanis, Afghanis, Iranians. Their arrival would radicalize and divide Europe. Poland and Italy elected anti-immigrant governments. Hungary and Denmark tightened their laws on migration. Merkel opted to lead the liberal bloc in Europe, calling on the European Union to require that other countries house their “fair share” of the migrants she had welcomed.

A majority complied at the time. But over the years, all have tightened their migration policies. In early November, France’s national assembly passed an immigration law proposed by its president, Emmanuel Macron. The law is meant to address the main problem with immigration enforcement in Europe—the category of migrants who in France are called OQTFs. To explain: Angry voters have compelled governments across Europe to tighten laws on labor migration. But governments supposedly cannot tighten laws on political asylum, because those are regulated by the 1951 United Nations Convention on Refugees. This means that virtually every economic migrant picked up in a smuggler boat off the Italian coast (or in one of the rescue boats sent by progressive foundations to ply the waters nearby) claims to be a victim of political persecution seeking asylum. This gives newcomers the right to a lengthy sojourn in Europe while awaiting an asylum hearing. Nowadays most such claims are rejected, but it is expensive and bureaucratically difficult to ship the applicants back to where they came from. The denied applicant is simply dismissed with a written notice that he is required to leave French territory (obligé de quitter le territoire français, or OQTF). He almost never does. Macron’s bill would, among other things, end this charade by restoring the criminal offense of illegally staying in the country, a measure that 82% of French citizens back.

The Macron bill is not particularly robust. It contains a giant loophole inserted at the behest of corporations—permitting the hiring of undocumented migrants for “occupations under pressure.” This may wind up undoing everything the bill achieves, much as the anti-discrimination provisions in the U.S. immigration reform of 1986 ended up promoting rather than controlling migration.

What is clear is the direction Europe wishes to go. Today Denmark, where financial support for asylum seekers is negligible and where it takes an average of 19 years for a migrant to become a citizen, gets about 2,000 asylum applications in an average year. Germany is expected to get 400,000 by the end of 2023. Denmark is the country on which virtually all European governments have announced they wish to pattern their policies. Germany is the country whose example other countries most wish to avoid.

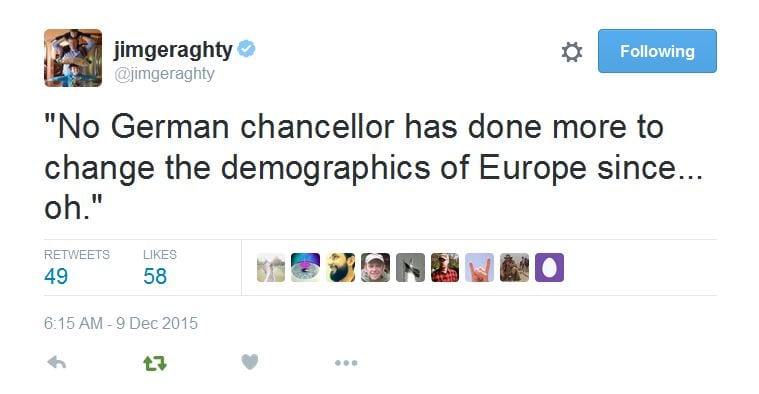

Merkel took a wrecking ball to the liberal values of postwar Germany, but hey, she made Time magazine’s “Woman of the Year” in 2015. I hope the tradeoff was worth it, both for her and Europe’s future, or the lack thereof. Or as Jim Geraghty tweeted in 2015: