UNEXPECTEDLY: Meta’s New Threads App is Censoring From Day One.

Threads is Meta’s latest and boldest attempt to go head-to-head with Twitter. Operating as an independent app, but at the moment requiring an Instagram login, Threads is the stage for public textual interactions and dialogues among users, linked to their Instagram profiles. Astonishingly, within less than a day of its debut on Thursday morning, Threads had already attracted a whopping 30 million sign-ups.

Mark Zuckerberg, Meta’s CEO, ushered in users with his inaugural post, “Let’s do this. Welcome to Threads.” He described Threads as a “friendly” alternative to Twitter, an app that lets people indulge in text-based conversations with a 500-character limit and the option to share links, photos, and videos.

Zuckerberg seems to be putting a lot of emphasis on keeping Threads congenial. He stated in a Wednesday post, “The goal is to keep it friendly as it expands. I think it’s possible and will ultimately be the key to its success.” He candidly went on to take a swipe at Twitter, suggesting that its lack of success is due to its desire to support more free speech.

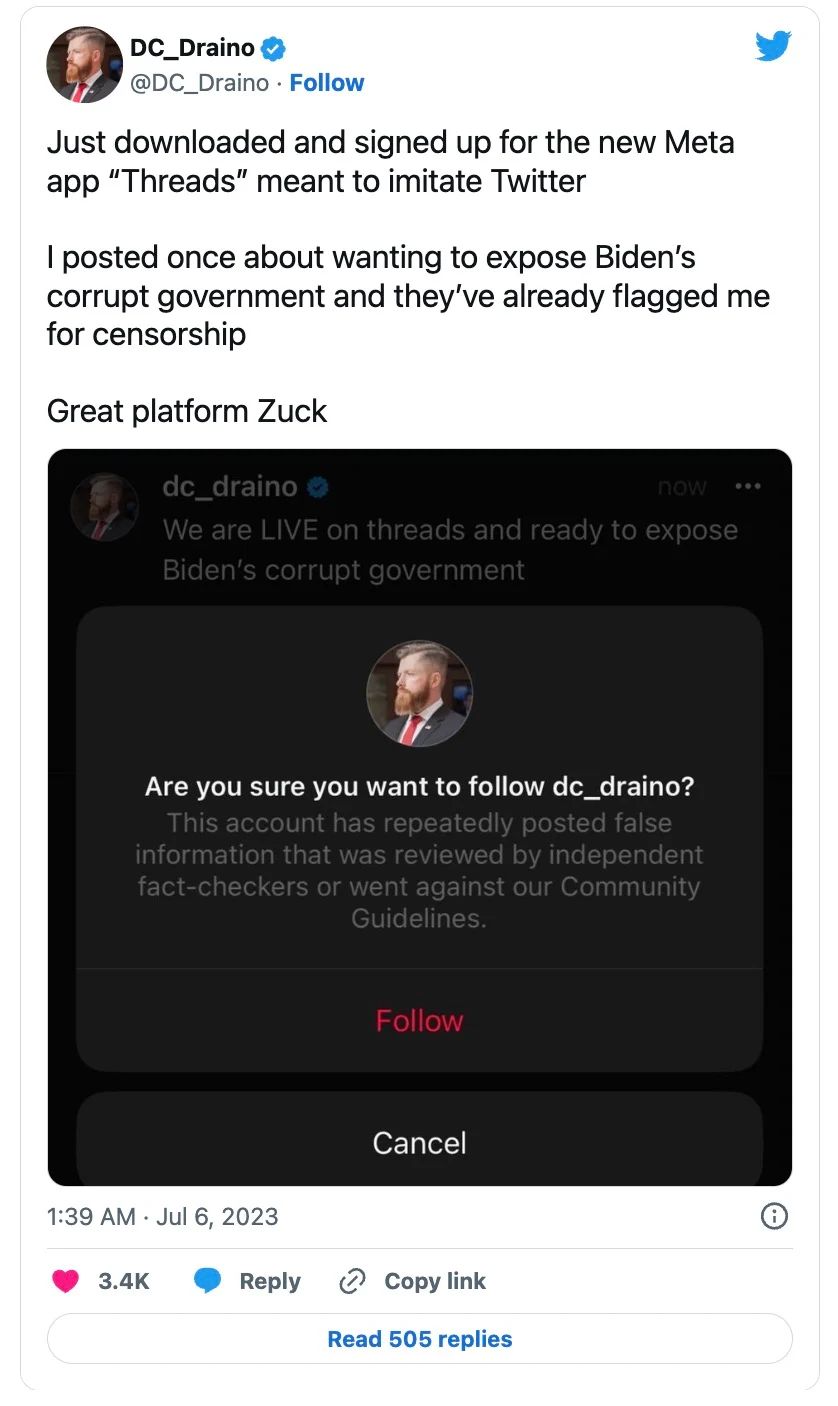

But of course, what Zuckerberg means when he calls for congeniality is censorship.

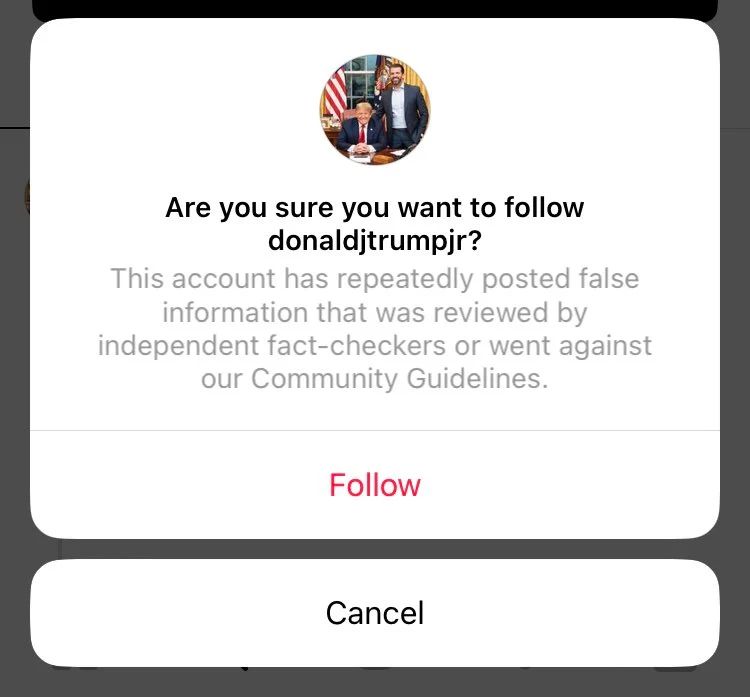

Just hours after launch, Threads was caught in the eye of the storm, with allegations of stealthy censorship and unavailability of user appeals.

Flashback: What Is To Be Done About Facebook?

From the company’s earliest days, Facebook’s leaders have adopted a remarkably consistent approach to the exposure of problems and missteps: a mercenary variation of the “ask for forgiveness, not permission” strategy. Any time the company does something irresponsible or privacy-violating, Zuckerberg issues an apology on Facebook and Sandberg appears on television programs to reassure an anxious world that Facebook will do better. As Zeynep Tufekci observed in Wired: “By 2008, Zuckerberg had written only four posts on Facebook’s blog: Every single one of them was an apology or an attempt to explain a decision that had upset users.”

But he kept doing it because it worked—until 2018. That year, Apple booted Facebook off of its app store for violating Apple’s privacy rules. Facebook had used an app to facilitate a research study wherein Facebook paid teenagers and some adults to let the company monitor everything they did on their mobile phones. That same year, there was a major hack of Facebook, this one affecting approximately 29 million Facebook users; the company issued its standard sorry-we-promise-to-do-better statement and changed nothing about its core business model.

Around the same time, as TechCrunch reported, Zuckerberg and other Facebook executives secretly “disappeared” their sent messages from their accounts, removing years’ worth of Facebook correspondence from other users’ mailboxes with no warning. Once caught out, the company claimed that it had done so for vaguely defined security reasons, but the lack of transparency by a company that insists that everyone should share everything was seen as hypocritical by many Facebook users.

As Peggy Noonan wrote in 2019: “Overthrow the Prince of Facebook...Break them up. Break them in two, in three; regulate them. Declare them to be what they’ve so successfully become: once a pleasure, now a utility. It all depends on Congress, which has been too stupid to move in te past and is too stupid to move competently now. That’s what’s slowed those of us who want reform, knowing how badly they’d do it. Yet now I find myself thinking: I don’t care. Do it incompetently, but do something.”

Somebody should write a book about this stuff.