NO. NEXT QUESTION? Are There Any Adults at the Washington Post?

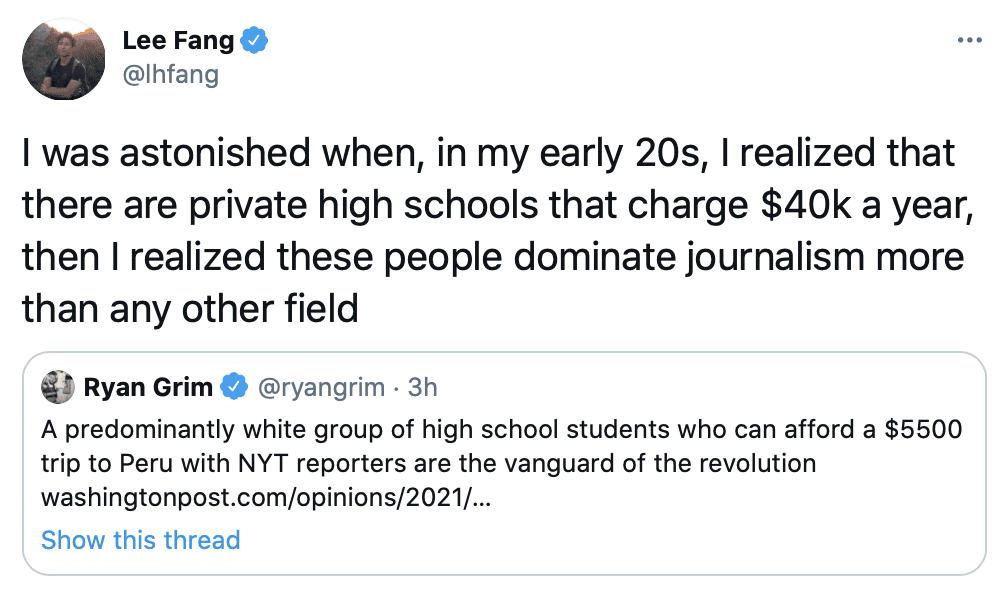

You may have noticed a bizarre trend at organizations whose staffs are full of younger liberals: Internal disputes aren’t kept internal anymore but are aired in public, on social media or in the press, with rampantly subordinate staff attacking their colleagues or decrying managerial decisions in full public view — and those actions apparently tolerated from the top.

In the most extreme cases, you get meltdowns like the one at the Dianne Morales campaign for mayor of New York, where staff went on strike to demand, among other things, that the campaign divert part of its budget away from campaigning into “community grocery giveaways.” But it’s especially a problem in the media, where so many employees have large social media followings they can use to put their employers on blast — and where those employers have (unwisely) cultivated a freewheeling social media culture where it’s common for reporters to comment on all sorts of matters unrelated to their coverage.

* * * * * * * * *

I hate that I’ve written so many paragraphs about this. I hate that I know so much about this dispute. It’s so high school, and it ought not to be any of our business. These are all internal HR matters. But Sonmez is explicit: She wages these fights in public because management is more responsive to that than when employees complain privately. By giving her “good friend” Weigel such a long suspension and doing nothing to her, management is only encouraging her and other Post employees to put their colleagues on blast more, which she has indeed been doing.

Airing internal workplace disputes in public like this is not okay, even when you are right on the merits. My statement isn’t just obvious, it’s how almost all organizations work. If you think your coworker sucks, you don’t tweet about it. That’s unprofessional. If you disagree with management’s personnel decisions, you don’t decry them to the public. That’s insubordinate. Organizations full of people who are publicly at each other’s throats can’t be effective. Your workplace is not Fleetwood Mac.

Even before the Times’ collective meltdown over Tom Cotton’s column in 2020, there were similar comparisons made about its own high school-like nature, such as Matthew Continetti’s 2014 Washington Free Beacon column:

Gossipy, catty, insular, cliquey, stressful, immature, cowardly, moody, underhanded, spiteful—the New York Times gives new meaning to the term “hostile workplace.” What has been said of the press—that it wields power without any sense of responsibility—is also a fair enough description of the young adult. And it is to high school, I think, that the New York Times is most aptly compared. The coverage of the Abramson firing reads at times like the plot of an episode of Saved By the Bell minus the sex: Someone always has a crazy idea, everyone’s feelings are always hurt, apologies and reconciliations are made and quickly sundered, confrontations are the subject of intense planning and preparation, and authority figures are youth-oriented, well-intentioned, bumbling, and inept.

Unexpectedly!

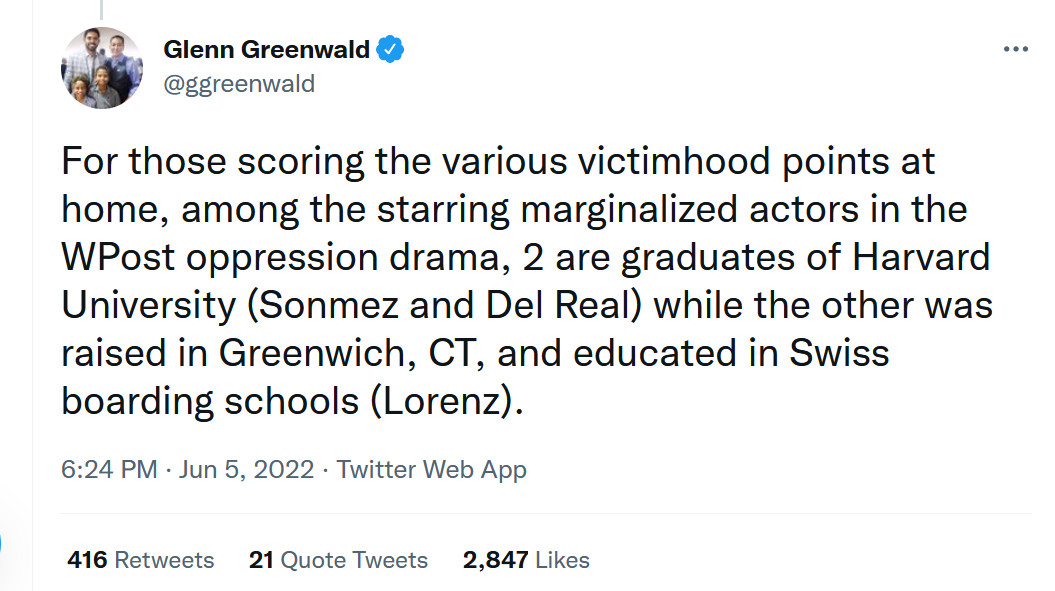

And as Glenn Greenwald noted over the weekend about the Post’s twitter spat:

Finally, note that the Fast Times at Ben Bradlee High drama at the Post this week is a distraction from what should be the real story emanating from the offices that once led to Watergate: Twitter saga obscures the Washington Post’s Taylor Lorenz scandal. “But the key point is this: Either Lorenz or her editors engaged in direct fabrication or a willful disregard for journalistic standards. The broader challenge is that those who run the Post have decided that Lorenz, and her continued shoddy reporting and broad generalizations, are worth the headache. Why they have decided as much is anyone’s guess. But as Lorenz continues to stretch the boundaries of ethical journalism, her Post colleagues will be the ones who share in the reputational damage.”