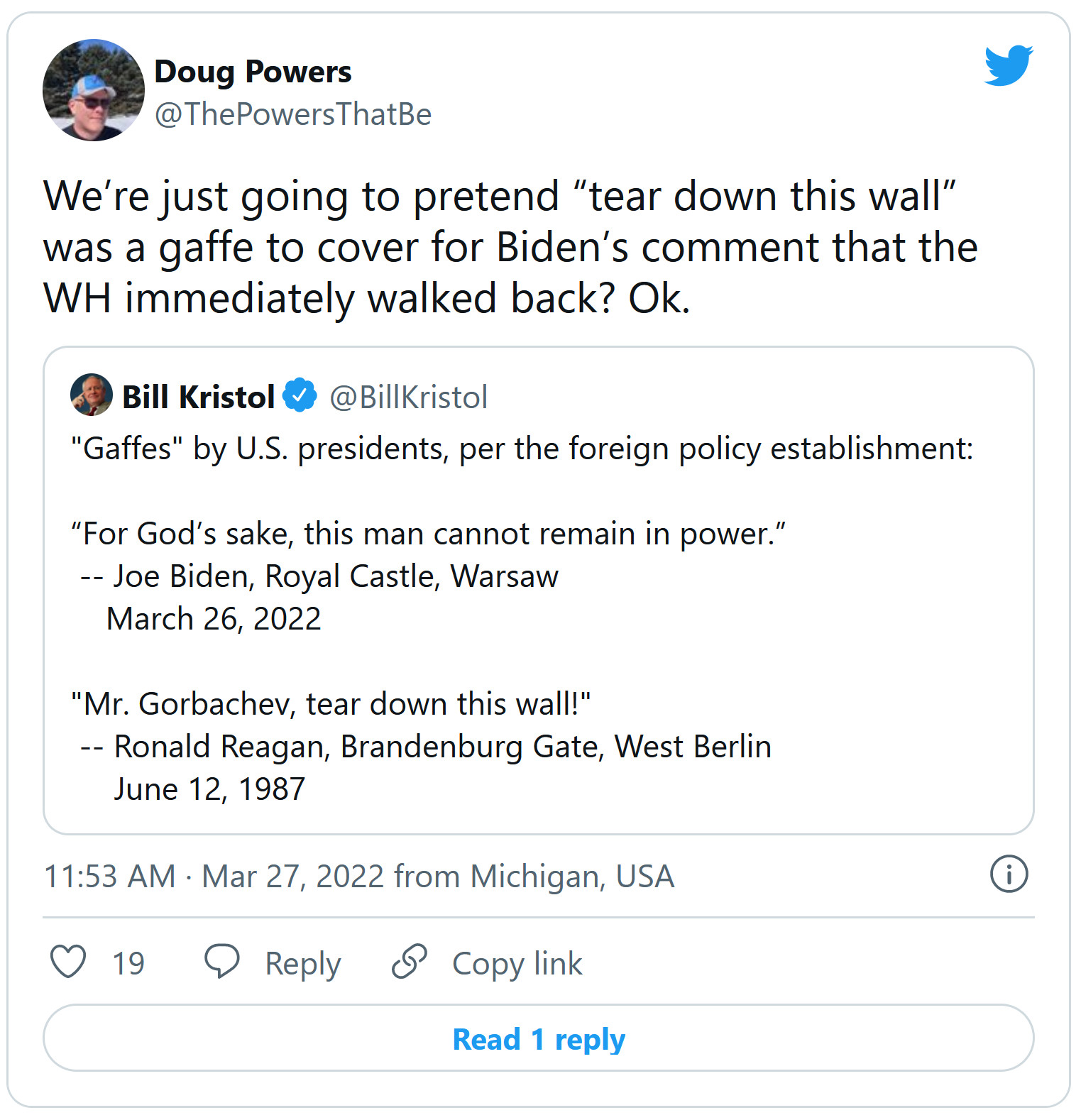

PAST PERFORMANCE IS NO GUARANTEE OF FUTURE RESULTS:

Shot:

Chaser:

“Well, there’s that passage about tearing down the Wall,” Reagan said. “That Wall has to come down. That’s what I’d like to say.”

The speech was circulated to the State Department and the NSC three weeks before it was to be delivered. For three weeks, State and the NSC fought the speech. They argued that it was crude. They claimed that it was unduly provocative. They asserted that the passage about the Wall amounted to a cruel gimmick, one that would unfairly raise Berliners’ hopes. There were telephone calls, memoranda, and meetings. State and the NSC submitted their own alternative drafts–as best I recall, there were seven–one of them composed by Kornblum. In each, the call for Gorbachev to tear down the Wall was missing.

This presented Tom Griscom with a problem. On the one hand, he had objections to the speech from virtually the entire foreign policy apparatus of the U.S. government. On the other, he had Ronald Reagan. The president liked the speech. Griscom had heard him say so. The president especially liked the passage about tearing down the Berlin Wall, the very part of the speech to which the foreign policy experts were most vehemently opposed. If that passage had to come out, it would be Griscom’s job to explain to Reagan why.

The week before the president’s departure, the battle reached a pitch. Every time State or the NSC registered a new objection to the speech, Griscom summoned me to his office, where he had me tell him, one more time, why I was convinced State and the NSC were wrong and the speech, as I had written it, was right. (On one of these occasions, Colin Powell, then national security adviser, was waiting in Griscom’s office for me. I held my ground as best I could.) Griscom was evidently waiting for an objection that he believed Ronald Reagan himself would find compelling. He never heard it. When the president departed for the Venice summit, he took with him the speech I had written.

On the very morning Air Force One left Venice for Berlin, the State Department and the National Security Council made a last effort to block the speech, forwarding yet another alternative draft. Griscom chose not to take it to the forward cabin. Air Force One landed. Hours later, President Reagan delivered his speech.

There is a school of thought that Ronald Reagan managed to look good only because he had clever writers putting words into his mouth. (Perhaps the leading exponent is my former colleague Peggy Noonan, who while a Reagan speechwriter appeared in a magazine article under a caption that said just that: “The woman who puts the words in the president’s mouth.”) There is a basic problem with this view. Jimmy Carter, Walter Mondale, George Bush, and Bob Dole all had clever writers. Why wasn’t one of them the Great Communicator?

Because we, his speechwriters, were not creating Reagan; we were stealing from him. Reagan’s policies were straightforward–he had been articulating them for two decades. When the State Department and the National Security Council began attempting to block my draft by submitting alternative drafts, they weakened their own case. Their drafts lacked boldness. They conveyed no sense of conviction. They had not stolen, as I had, from Frau Elz–and from Ronald Reagan.

—“Tearing Down That Wall,” Peter Robinson in The Weekly Standard, then-edited by Bill Kristol, June 23rd, 1997.

Related: Blinken continues cleanup of Biden’s Putin ‘cannot remain in power’ remark.

More: Zelensky Responds to Joe Biden’s ‘Historic’ NATO Speech in Less Than Flattering Terms.