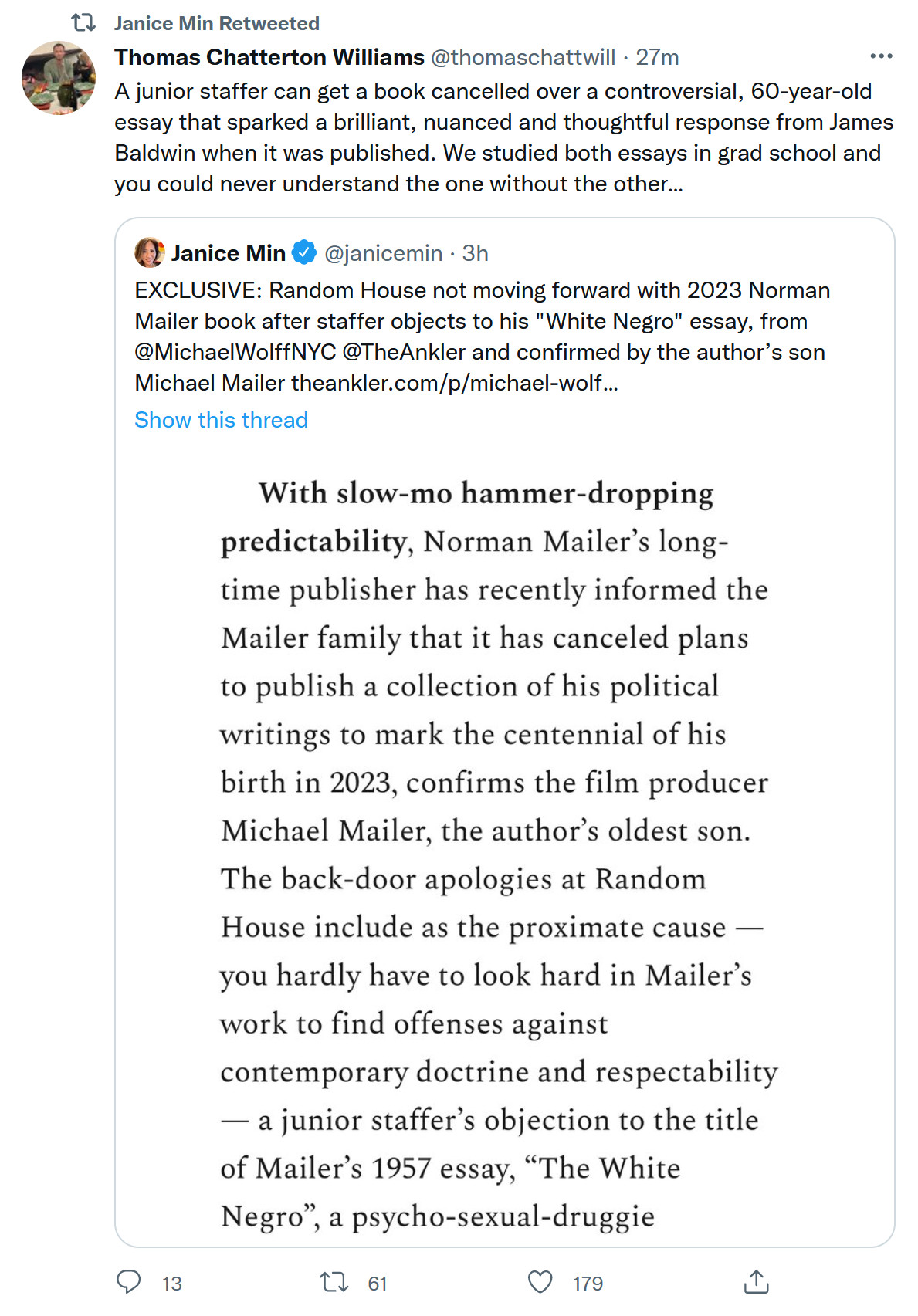

THIS YEAR, CANCEL CULTURE COMES FOR — hang on, checking notes — NORMAN MAILER:

Unfortunately, Wolff’s article is behind a Substack subscriber-only paywall, but we’ve seen this movie numerous times before by now, including Woody Allen’s autobiography and (almost) Jordan Peterson’s sequel to his best-selling 12 Rules for Life. It’s all the more astonishing when Mailer’s “White Negro” essay is readily found online, and Baldwin’s response is available for Esquire subscribers.

Regarding the former, Roger Kimball wrote in 1997:

Mailer’s flirtation with criminals like Gary Gilmore and Jack Abbott must be seen as the fulfillment of his celebration of the “psychopath” as an existential hero. In his notorious essay “The White Negro: Superficial Reflections on the Hipster,” first published in Dissent in 1957, Mailer definitively articulated an ethic that underlies not only his own view of the world but also the view that would inform the cultural revolution of the 1960s. In tone, “The White Negro” is a panoply of “existentialist” rant. In content, it is a manifesto on behalf of moral nihilism. Mailer speaks casually of “the totalitarian tissues of American society” and invokes “the psychic havoc of the concentration camps and the atom bomb upon the unconscious mind of almost everyone alive in these years.” The only authentic response to this situation, he says, is “to divorce oneself from society” and “to encourage the psychopath in oneself.” This is the strategy of “the hipster,” who has “absorbed the existentialist synapses of the Negro, and [who] for practical purposes could be considered a white Negro.” (Mailer’s stereotypical portrayal of blacks as beastlike sexual athletes is one of the many distasteful things about the essay.)

The rest of “The White Negro” is a glorification of the hipster and his ethic of promiscuous sex, drug-taking, and criminal violence. The hipster, Mailer explains, is part of “an elite with the potential ruthlessness of an elite, and a language most adolescents can understand instinctively, for the hipster’s intense view of existence matches their experience and their desire to rebel.” Mailer conjures the image—it is what made the essay infamous—of eighteen-year-old hoodlums who “beat in the brains of a candy-store keeper.” For Mailer such behavior is acceptable, even laudable, because the psychopath, by murdering, demonstrates his “courage” and “purge[s] his violence.” To the objection that it does not take much courage to kill someone older and weaker, Mailer explains that “one murders not only a weak fifty-year-old man but an institution as well, one violates private property, one enters into a new relation with the police and introduces a dangerous element into one’s life.” Mailer goes on to explain that “at bottom, the drama of the psychopath is that he seeks love.” Not, however, “love as the search for a mate, but love as the search for an orgasm more apocalyptic than the one which preceded it. Orgasm is his therapy—he knows at the seed of his being that good orgasm opens his possibilities and bad orgasm imprisons him.” This is one reason that the hipster adores jazz: “jazz,” Mailer tells us, “is orgasm.” The hipster’s quest “for absolute sexual freedom” entails the necessity of “becoming a sexual outlaw.”

It is not only sexual morality that the hipster discards. “Hip abdicates from any conventional moral responsibility because it would argue that the results of our actions are unforeseeable, and so we cannot know if we do good or bad. … The only Hip morality … is to do what one feels whenever and wherever it is possible, and … to be engaged in one primal battle: to open the limits of the possible for oneself, for oneself alone, because that is one’s need.”

“The White Negro” adumbrates practically everything that went wrong with American society under the assault of left-wing radicalism in the 1960s, from the addiction to violence, drugs, pop music, and sexual polymorphism, to the moral idiocy, jejune anti-Americanism, and mindless glorification of narcissistic irresponsibility and extreme states of experience. Although many critics took issue with Mailer’s exoneration of violence, the real message of the essay—if it feels good, do it!—was just then beginning to sweep the country with irresistible force. “The White Negro” represented an important opening salvo in the war on convention, restraint, and traditional morality. This, not his literary accomplishment, was the ultimate secret of Mailer’s broad appeal. Mailer, as Joseph Epstein observed, “was one of the key men responsible for releasing the Dionysian strain in American life.” He promised his readers what they longed to hear: that ultimate, self-centered ecstasy was theirs for the taking. Mailer once said that he would “settle for nothing less than making a revolution in the consciousness of our time.” He did not make the revolution, but he assuredly became one of its most egregious emblems.

Apparently, today’s puritanical left aren’t interested in exploring the worldview of their grandfathers to see how we got here, and are content to airbrush Mailer from history, 14 years after his death. Hopefully, as with Woody Allen’s autobiography, a smaller publisher will release what Random House was bullied out of publishing. In the meantime, as Andrew Sullivan asked his fellow leftists last year: What Happened To You?