In my practice as a psychotherapist, I’ve seen an increase of depression in young men who feel emasculated in a society that is hostile to masculinity. New guidelines from the American Psychological Association defining “traditional masculinity” as a pathological state are likely only to make matters worse.

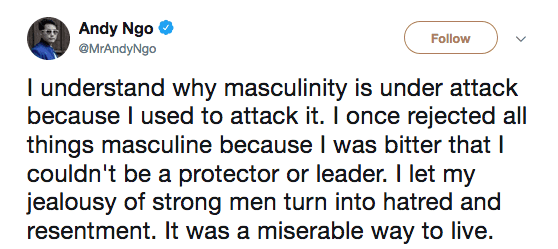

True, over the past half-century ideas about femininity and masculinity have evolved, sometimes for the better. But the APA guidelines demonize masculinity rather than embracing its positive aspects. In a press release, the APA asserts flatly that “traditional masculinity—marked by stoicism, competitiveness, dominance and aggression—is, on the whole, harmful.” The APA claims that masculinity is to blame for the oppression and abuse of women.

The report encourages clinicians to evaluate masculinity as an evil to be tamed, rather than a force to be integrated. “Although the majority of young men may not identify with explicit sexist beliefs,” it states, “for some men, sexism may become deeply engrained in their construction of masculinity.” The association urges therapists to help men “identify how they have been harmed by discrimination against those who are gender nonconforming”—an ideological claim transformed into a clinical treatment recommendation.

The truth is that masculine traits such as aggression, competitiveness and protective vigilance not only can be positive, but also have a biological basis. Boys and men produce far more testosterone, which is associated biologically and behaviorally with increased aggression and competitiveness. They also produce more vasopressin, a hormone originating in the brain that makes men aggressively protective of their loved ones.

The same goes for feminine traits such as nurturing and emotional sensitivity. Women produce more oxytocin when they nurture their children than men, and the hormone affects men and women differently. Oxytocin makes women more sensitive and empathic, while men become more playfully, tactually stimulating with their children, encouraging resilience. These differences between men and women complement each other, allowing a couple to nurture and challenge their offspring.

Modern society is also too often derisive toward women who embrace their biological tendencies, labeling them abnormal or unhealthy. Women who choose to stay home with their children can feel harshly judged, contributing to postpartum conflict, anxiety and depression.

What’s unhealthy isn’t masculinity or femininity but the demeaning of masculine men and feminine women. The first of the new APA guidelines urges psychologists “to recognize that masculinities are constructed based on social, cultural, and contextual norms,” as if biology had nothing to do with it. Another guideline explicitly scoffs at “binary notions of gender identity as tied to biology.”

From a mental-health perspective, it can be beneficial for women to embrace masculine traits and for men to express feminine ones. Every person will have some mix of the two. But that doesn’t change the reality that women tend to be feminine and men tend to be masculine. Why can’t the APA acknowledge biology while seeing femininity and masculinity on a spectrum?

Why, indeed? Possibly because the APA is run by people who are working out their own psychological issues at the expense of everyone else. The question is why the rest of us allow that.